Sign up for LTI Korea's Newsletter

to stay up to date on Korean Literature Now's issues, events, and contests.

Dream of Me

by Kim, Mella Translated by Archana Madhavan June 14, 2022

창작과 비평 195호

Kim, Mella

Every time we sang “When You and I Were Young, Maggie” in music class, the same lines piqued my curiosity. The green grove is gone from the hill,

Maggie,

Why Maggie, though? The song likely wasn’t referring to the wide-mouthed, whiskered catfish we called megi. Sitting in that music room where the sunlight did not reach and under those fluorescent lights that were dying out, I opened my mouth and sang, The creaking old mill is still…

Maggie,

The song seemed to plunge as though it were suddenly falling off a steep cliff and my heart skipped a beat every time. The American name “Maggie” was written phonetically in Korean but the music score didn’t include the original song lyrics, so there was no way of knowing anything about Maggie or the person who missed her. I didn’t look for answers nor did I ask anyone about the mystery behind the name. I left it alone, an unsolvable puzzle.

A similar question came to mind when I sang “Oh! Susanna.”

I come from Alabama

With a banjo on my knee

I’m going to Louisiana

My true love for to see.

A banjo on the knee of a person coming to see Susanna. What’s a banjo? I wasn’t sure, but the word seemed to be held together by stiff hinges and gave off a whiff of rusted iron. Like a confession one overhears while half-asleep, the words “banjo” and “Maggie” were shrouded in secret shadow. I meandered to my heart’s content in the maze of those songs. I didn’t come from some city in some state in South Korea—didn’t the place I come from have a clear stream flowing through it and scarlet alpenroses? Das Berner Oberland, Oberland. As I mumbled words in a foreign language I didn’t even understand, I imagined Maggie and Susanna running away to “beautiful Bern.” In my fantasy, Maggie met Susanna, who lived in another song, and headed to the alpenroses with a banjo on her knee.

“Well, you came,” I said to Chamba.

The snow on the trail came up to our calves and Chamba was trying not to fall. Chamba smiled reluctantly, as if to say, How much longer are you going to make me walk on a road like this in this kind of weather? Snow was coming down in thick, beautiful flakes. The two of us walked and headed up Namsan trail in search of a Coffee Pori. I remembered the last place I’d had coffee milk like that, and so, we arrived at Namsan trail’s last supermarket. Namsan Trail’s Last Supermarket—that was the name of the place. Coffee milk in round plastic containers or in square paper cartons could be found anywhere, but I only wanted the kind that came in a triangular plastic pack.

“You have to roll me down. I can’t walk anymore,” Chamba said.

Chamba was standing under the awning of the supermarket after finishing their coffee milk. We could no longer see the footprints we had left on our way up; they were already covered by the snow. Unable to withstand its own weight, a load of snow fell from the tin rain gutter that was affixed to the wall. I looked up at the mountain ridge where the snowflakes were falling. The sky was blue and still. In the far distance, a blue surf washed over the land, slowly diluting until it reached the ridge of the snow-covered mountain and turned completely white, like a shallow wave flooding a beach. Near and far, the land was completely covered in snow; even the asphalt on the road and the branches of the roadside trees were thickly blanketed. It was almost as if the trees, tired out by exhaust fumes and relentless neon signs, had covered themselves up with snow and were now resting. Is my dead self resting like that too? I wondered.

I told Chamba that I would get started first.

“Oink oink, follow my lead.” I made pig noises and folded both of my hands over my chest.

Like a dry leaf pierced through by an irrevocable wind, I fell into the snow.

*

When I was dying, Chamba showed up and had sung me a song. They’d played an instrument that looked similar to a guitar but wasn’t a guitar, an instrument that was like a great-great-grandmother to a guitar’s second cousin or something, and they’d sung “Oh! Susanna.”

I come from Alabama

With a banjo on my knee

I’m going to Louisiana

My true love for to see.

Even though Chamba—whose hair was combed back neatly and cut so short that their widow’s peak stood out—was dressed smartly in a navy-blue china jacket and handkerchief, they were dreadfully tone deaf and, at first listen, didn’t seem to know how to play the banjo. All they did was sweep their fingers up and down the metal strings of the instrument with its round body and copper-colored hooks, not even keeping to the key or the beat of the song.

“Are you going to keep staring at me?” Chamba asked.

By then, we had levitated off the ground and were floating near the ceiling. Below me and Chamba, my dead self lay unconscious on the ground. At some point, I had left my body. I felt exactly like I did when the music led up to The green grove is gone from the hill,

Maggie,

as if the rhythm enveloping me had transformed all at once into a different kind of current, without a single word changing. Like how a volleyball might feel when it skips the stages of receive, toss, and spike and instead flies directly over the net in an unorthodox attack. I wasn’t scared or in pain. It’s just that there seemed to be a vague caramel scent between my out-of-body self and my prone self. That was probably because of the caramel in the Almond Crunch Cranberry Choco Bar I had been eating just before losing consciousness. The moment that crushed-almond confection—its dried cranberries with that hardened nugget of chocolate—took the wrong path to my throat, the ligaments of my trachea swelled and seemed to pierce through the husk of my body, like a seedling sprouting from its growing point. Even while lying face down on the foam mat, choking, I was aware that this situation could end in my death. Did that mean that on my death certificate the cause of death would be noted as “respiratory obstruction and suffocation due to a foreign object”? Then what about my first attempt, when I tried overdosing on pills? What about my life’s chokeholds, one after the other; those small and large humiliations of the past that made me want to tear myself apart and set myself on fire? My biorhythm, in a word, that was different during the summer and winter? My bipolar psyche? My disordered and fitful sleeping, caused by my willpower having run completely dry? My relationships, roiling like the jigger valve of a pressure cooker, splayed like a sideways number eight?

Relationships, that is, when someone asks to “Explain the causal relationship” in this case, what was the cause?

Without having any way of explaining the reason I had become a jobless, thirty-something-year-old woman living alone; or this world in which I, bracing myself for the end, swallowed a bunch of sleeping pills and, waking up three days later, thought, I can’t die like this, (How is it that during those three days of oscillating between life and death, not a single person contacted me, except for the credit card company texting me about some promo?) and where absolutely no one was curious about my well-being; or the black comedy of my choking to death on a buy-one, get-one free chocolate bar that I had eaten too quickly, just as I had made up my mind to pull myself together and live; or the cause in this twisted causal relationship that, although nobody’s life or death exists to make others laugh, made even me, the one in question, laugh bitterly . . .

. . . my body oozed from one point to another, just like paint being squeezed from a tube. Soon after, Chamba showed up and started singing to me.

“Excuse me, are you an angel?” I asked, polite even in that bewildering situation. I figured they were an angel or something similar, given that they had shown up at that specific moment.

“I’ll introduce myself later. You have thirty seconds left. In fifteen seconds, your heart will stop beating, then the oxygen supply to your brain will be cut off. After that, you’ll turn into a Traveler and be on your way,” Chamba said, moving their feet slowly in midair.

My feet, too, swayed like seaweed in the ocean current. I lay unconscious below, my face turning blue from cyanosis. Scattered on top of the foam mat, which was stained with splotches of hot sauce, there were years’ worth of prescription medication packets and a square notebook bound in thick thread. Oh, I guess I just left that there. What if they think it’s a suicide note? This was most certainly an accident. I stretched out my arm to try to get rid of that trace of myself: the thing I had written on craft paper with a thick-nibbed pen (“I want to be the one to pull the plug on myself”). That’s when Chamba unfurled an opera-pink handkerchief and covered my face. That is, on my dying body. Then, everything grew bright before my out-of-body self’s eyes and, like a person being shoved while trying to transfer subway lines during rush hour, I was thrust out of the room. Right through a concrete wall.

I

am afraid of heights,

I thought, but before I had any time to feel anxiety or terror, my body was rising up and up, like moisture on the ground evaporating into the atmosphere by the heat of the sun. As if I had become, not a person or a solid mass, but a single, high-speed current. A particle—even with all that was happening, I had come up with a word to describe my situation. Split and split until it could be split no more, a simple, fundamental why

why did you do it why did you do it why did you do it

why did you do it

That’s what my mother had said while wringing my arm, a year ago when she came to see me in the emergency room after my first attempt. Will it be Mother again this time? Did it have to be her? I lived isolated from the world and didn’t expect anything in the mail; I had even signed up for autopay so my utility bills would be deducted from my bank account. My one neighbor had moved out a few months ago, too. Even as I thought, Oh well, this has already happened, what’s one more nail in the coffin?, I still wanted to avoid the worst, so I tried to come up with someone else (not Mother) who could find my body. Then, like being caught in the strong current of a winding river, I felt myself suddenly twisting, flying over something, crossing through cold and warm air, and then going down, down. The cells of my body had already begun to die.

*

Even with the snow falling, the midday sun appeared high in the sky. The air was just warm enough that the snow didn’t melt and cold enough that the snow crystals didn’t clump together; in this perfectly mixed climate, Chamba and I walked a pace apart. Maybe my moment of floating in midair before dying was some kind of perk, like a discount coupon that new customers get for their first order, but now I was plodding along with my own two feet clad in snow boots. Seeing a crossroad that looked like a polar ice block, I thought of snowmobiles with their skis and snow chains. It would have been perfect to ride a snowmobile down a road like this. But in the city of my imagination, all engine-powered transportation was non-operational. This seemed to be due to Chamba’s influence. Chamba, who’d pulled the plug on themselves in their own car, disliked motor vehicles. They refused buses and motorcycles too, and only wanted to travel by their own two feet. I had my doubts as to whether a person like them could guide a Traveler like me.

“Are there a lot of people like me?” I asked as I watched the boot of my outstretched foot bury itself in the snow.

Chamba was walking ahead of me, wearing sneakers with crampons attached to them. “Like what?”

“Dead.”

Dead like me. That is, not dead after actually attempting to die, but dead unexpectedly. Dead by a surprise attack unfairly launched by someone else, even though they might have already planned a death of their own; dead, like squares of toilet paper torn at random, not neatly along the perforated line between mine/someone else’s will.

“We say they awoke here. ‘Our friend Lazarus sleepeth, but I go, that I may awake him out of sleep,’” Chamba said, adjusting their goggles.

Who’s Lazarus? The name sounds vaguely familiar. Did I see it in a Spanish movie? Lazarus Diego Garcia?

As I muttered to myself, Chamba stretched out a gloved hand. “Come forth, Lazarus! You don’t know this? Jerusalem’s Lazarus?”

I said I didn’t.

“You know about Jerusalem, don’t you? Israel, religion, Taj Mahal.”

The Taj Mahal is something else, I thought, and averted my gaze to Chamba’s breast pocket. Unlike when I first saw them, Chamba was wearing thick racing coveralls. The word “chambachamba” was embroidered in yellow thread on their breast pocket; whenever I saw it, I always pronounced it “chamba” in my head.

“It’s from the Bible. Since you said you’d been to church.”

“A couple times, long ago,” I said.

Chamba stopped and pulled off their open-finger gloves.

“Or we leave it as parentheses, too, without using specific words. Awakened person, or parentheses.”

“Parentheses?”

“Neither blame nor praise, just parentheses. Before judgment, parentheses,” Chamba said, wiping the lens of their goggles with those gloves of theirs that exposed the tips of their fingers.

In that moment, I saw Chamba’s face clearly. Eyes glinting with indifference, as if to say nothing good would come out of meeting their gaze; below their eyes, marks left by the goggles. Cheeks that were neither narrow nor wide. A chin that could have been used in a physiognomy textbook as an example of a jawline that would bring one good fortune later in life. How old are they? What about their gender? Their voice sounded like that of a middle-aged man, but the curves of their clothed upper body suggested a woman. Regardless of their gender, they were not the type to have been doused in torrents of hormones that caused secondary sex characteristics. In other words, they were simply Chamba, who looked really good in a motorcycle racing suit.

“What?”

Chamba looked at me. I turned away.

“Do you want to know?” Chamba asked, stretching the band of the goggles behind their head.

I shrugged. But, unable to hold back my curiosity, I scanned the white zippers hanging from Chamba’s clothing. Chamba’s clothing, which was connected top and bottom, had several zippers (including, it appeared, near the crotch and buttocks, presumably for the purpose of making it easy to use the bathroom) and at their chest and thighs were three opera-pink bands that stood out sharply against the snowy white landscape.

“Round parentheses? Or pointy ones?” I asked to change the subject, as if to say, Your gender is of no importance to me. I also smiled slightly, as though to add, But if you want us to grow a little closer, you’d pull down your scarf and let me check if you have an Adam’s apple.

“Empty parentheses. They’re left empty.”

Chamba raised two hands to chest height and made a sign indicating parentheses. They adjusted their hat which had a fluffy pom dangling from it. Then, they started walking again and I followed suit. From atop the snow-covered streetlights, tiny-winged birds took flight. I kept forgetting that Chamba could sense my thoughts. It’s not that my every thought was completely transparent like water in a glass, Chamba said, but they could pick up on my condition as a Traveler, which was necessary for a Guide to know. They said a simple way to think about it was if I saw myself as a website that we were both accessing simultaneously; in reality, Chamba couldn’t explain in much more detail themselves. When I asked them if they heard my thoughts in their ears like a narrator’s voice in a movie, or if they saw it in front of their eyes like words printed in a book, they responded, Who thinks like that? and then added, It’s unconscious, a natural flow, like how your body moves forward when your foot takes a step. That explanation was even harder for me to understand. How could the neural activity of our separate, individual brains be interconnected as one? Like a math exam I had only memorized the formulas and thus got every applied question wrong, I couldn’t easily grasp the fundamentals of being a Traveler, such as my thoughts being connected to Chamba’s and the fact that I could go into other people’s dreams from my imagination. As we neared the first dream destination, I grew worried that I’d made the wrong choice.

I planned to visit Gyuhee’s dream. Knowing her, I didn’t think she would be one to suffer from lifelong trauma if she discovered my body. My middle school friend whom I ate lunch with, both of us glancing sideways at each other’s side dishes to see how much was left. The pastor’s daughter Choi Gyuhee, who came to my house every Saturday afternoon to take me to the church youth group.

I wasn’t doing this just to ask her to find my body. Gyuhee and I shared a close friendship during our teens. I was doing this because we were tteokbokki mates—if one of us wanted to go to Dongbaek Tteokbokki, the other came along, no questions asked. Even if it was the second day of her period, even if she hadn’t washed her hair in three days, she’d stick an overnight pad in her panties, pull a hat over her hair, and come along. I was doing this because it was Choi Gyuhee, who knew perfectly well that while you could enjoy samgyeopsal BBQ by yourself, instant tteokbokki rice cakes tasted best when you shared two servings with a friend and had it with some fried rice. Sometimes she’d come on a Saturday I didn’t want to go to church and I would ignore her even though I heard the doorbell ring, but Gyuhee experienced that once in a while anyway while evangelizing kids of her own age. Gyuhee and I were assigned to different high schools and thus grew naturally apart. After we started college, we called each other up to eat seaweed rolls dunked in tteokbokki sauce whenever we grew tired of our social lives as adults. We fretted together over an extra order of glass noodles at Dongbaek Tteokbokki that time Gyuhee said she was going to quit her job, learn how to bake, and open up her own dessert shop; or that time she debated whether to marry her first love whom she kept breaking up and getting back together with. Rather than going with choices that minimized loss, we put our minds together to figure out what would bring her the most satisfaction even if it ended up a loss. Gyuhee was the talker and I was the listener, but whenever I asked roundabout questions to test her (Would you still be my friend if I completely screwed up my life and became homeless? What about if I were falsely charged with a crime and ended up on the run? What if I dyed my hair rainbow and got a tattoo of a dragon on my arms and . . . What if I said I liked girls, would you still be able to see me as a friend?), she’d replied, as if they were the easiest questions in the world, As long as you don’t ask me to be the guarantor on a loan you’ve taken out, I’ll be your friend until we’re both dead and turned to ash.

“She said she’d give up a toe for me. She couldn’t give up a whole foot, but she said she’d give up a toe to save my life, no problem.”

I sat down on a stool and looked around Dongbaek Tteokbokki. The restaurant, which was in an alley across the street from Dongbaek Girls’ Middle School, hadn’t changed much from the past. The open, wall-less first-floor interior and the plaster surface covered in a mess of handwritten notes left behind by guests; the checkered tablecloth and gas burners on each table. If there was one thing that had changed, it was that the owner of the restaurant, the ajeossi who wore a green fishing vest year-round and took our orders, was nowhere to be seen. Instead, you had to order through an automatic kiosk.

“Gyuhee and I are meeting up after a long time and creating memories. She turns into a sweetheart if you give her two seaweed rolls.”

I tucked a hand between my thighs and looked toward the kitchen, from which wafted the scent of gochujang seasoning. I was worried that the taste of the tteokbokki had changed but, truth is, I didn’t remember what it tasted like in the past.

“You said eating was good, right? Food that we’d eaten together?” I asked Chamba.

Chamba set their olive-colored banjo case on an empty seat, removed their hat with the pom on it, and placed it on top.

“There is a high probability of success, yes,” Chamba said and then asked, “Apron?”

On the opposite wall, there were several gochujang-colored aprons hanging on a peg, one on top of another. Staring at the blue flame surging from the burner, I thought, How should I tell her? Should I spill the whole truth and plead with a plaintive expression on my face? Gyuhee-ya, please come to me. Please help me. Or should I create a nightmare and scare her? If you don’t find me in twelve hours, a member of your family will die! Maybe a dream where all her teeth fall out as she’s eating tteokbokki, or her apron catching fire from the gas burner, or a ferocious beast running into the restaurant. How should I tell her? I thought as I tasted the simmering tteokbokki.

“She’s filled with the Holy Spirit, so she’ll be fine. She was born Christian,” I explained to Chamba, who was filling a stainless-steel cup with water.

After handing me the cup, Chamba brought back a dish filled with white pickled radish. The melamine dish was chipped and singed black at the brim.

“She drinks a little, too. She’d hide soju bottles in her desk drawer without her father knowing and have it with crushed-up dry ramen. She said being drunk was good for repenting, too. So even if I scare her, she’ll be fine after she has a drink and prays.”

I kept thinking about Gyuhee finding me. No matter how strong her faith, wouldn’t seeing a dead person be a shock to her? Had Gyuhee ever seen a dead person? Were her mother and father well? Last holiday, she had said her mother had gotten knee surgery and couldn’t even go to the bathroom by herself. I suddenly recalled a memory of me screaming at the sight of a dead baby mouse in the toilet of our middle school restroom. I was the one who had discovered the mouse. Gyuhee, who was doing her business in the next stall over, was so startled by my scream that she took off running to the security office, without even realizing that the hem of her skirt was rolled into the shorts she wore underneath. Any time I was sick or my mind was troubled, I would dream of that dead mouse in the toilet with its two eyes closed. I would dream that I was going up and down the school stairs again and again, looking for a clean toilet. Would Gyuhee have dreams like that? What memories did she return to when she was sad or sick?

“I think it’s done.”

Chamba tilted their head to look under the pan in order to adjust the flame. The well-cooked tteok were simmering in a sauce containing plum extract.

“I once asked Gyuhee, ‘Do you really believe the Virgin Mary gave birth to a child she conceived on her own?’” I told Chamba, who was stirring the glass noodles with their chopsticks.

“And?”

“She said she didn’t know because she’d never been pregnant herself.”

Chamba filled my dish with tteok and seaweed rolls, and handed it to me. I looked down at the steaming dish. Does Gyuhee know now? Would Gyuhee, who was raising a five-year-old son and a three-year-old daughter, remember the question I asked her after poking her in the back with my pen? During study hall, when I hadn’t wanted to study and couldn’t disturb the others, I had nudged the pastor’s daughter Choi Gyuhee and pestered her to talk to me about the Bible. Gyuhee stopped the diligent work she was putting into memorizing English vocabulary, so much so that her white paper was turning black with scribbled words, and turned around to look at me. She said, I believe it, more or less. What are you curious about? I tested her with the contents of a school library book (There Is No Bible) that I had found in a large sack meant for scrap material. The Bible says that if you do it with a man when you’re menstruating, both the man and the woman should be put to death, and at church they say the woman should keep her mouth shut and obey the man? And then last time, the pastor said that if you die by suicide, you go to hell. Do you think that’s right? Wouldn’t you think you’d treat a person who died because they were suffering even better? What did Gyuhee say back then? Did she laugh? Did she get angry? Did she tell me to shut up and get back to memorizing English vocabulary?

“The problem is . . .” Chamba began. They had put two pieces of tteok in their mouth and, perhaps finding them hot, bitten into some of the white pickled radish and, still finding it hot, gulped down some water. “You need to eat all of this before you can have the fried rice.”

I used my chopsticks to divide the swollen seaweed rolls into two, then three, pieces. Was that really so hard? She said she’d give up her toe for me. This was much easier than cutting off a toe. About as hard as telling someone to tear the sticker off a package and dispose of it? Was it too much to ask for something that simple, like tearing off the invoice sticker because I didn’t want the paper with my name and address to be spread out all over the world? Because a person’s body, their corpse, is more important than their personal information. Who should I ask, what words should I use, to beg for someone to find me before my body starts rotting, before it becomes damaged, so I can quietly move on from this world?

“I just remembered why we shouldn’t have gone to Gyuhee,” I said, looking at Chamba whose cheeks were flushed from the heat of the pan.

“She was tall, you know. When our music teacher told Gyuhee to take a look at the fluorescent lights and stop them from flickering, Gyuhee said anyone could be as tall as her if they got up on a chair. So it didn’t have to be her specifically.”

*

There were no cars coming or going, but still we stood at the crosswalk and waited for the light to turn green. Snow gathered on the narrow leaves of the yew trees next to the traffic light. Snow settled on top of the fallen sycamore leaves that had blown in from somewhere, on top of the thick iron nails that were driven into the telephone poles for climbing, and on the small heads of those nails, too. It covered the cars’ glass and metal alloy exteriors, so you could only make out the vague shape of their roofs and bonnets. Snowflakes descended along herringbone tracks made by rubber car tires. Next to them, Chamba’s and my shadows lay crookedly, our waists stretched long.

As we crossed the street, its lanes completely covered up by the snow, I asked Chamba, “What were the other parentheses like? Did you ever visit someone else’s dream?”

After Gyuhee, I was thinking about Semo, whose name meant “triangle.” I wondered if a lover whom I’d been naked in front of would be better than a friend whom I’d exchanged greetings with three or four times a year whenever the seasons changed. In any case, I thought I wouldn’t feel as bad if it were a lover, someone who spewed curses like a competition whenever we fought. When I thought of who it would be okay to hurt a little, who would have more memories of us loving each other than of us hurting each other, Semo was the only person who came to mind.

“There was once an old granny in her eighties. We visited her nephew, in a memory where they were eating banana-ppang. The granny’s memory was hazy so we wandered around for quite a while.”

“Is that like bungeo-ppang?”

“It’s a bit different. Bungeo-ppang is a fish-shaped pastry with red bean paste or cream in it. Banana-ppang is banana shaped and has no filling, just dough. Now the nephew lives near a market that sells banana-ppang.”

“Nice foreshadowing. Was that granny alone too?”

“She was alone and she awoke.”

“Awoke” meant pulling the plug on yourself. Or was it used in situations when you died alone and there was no one to let the world know of your death? Or maybe anyone could become a Traveler when they died?

“There are criteria,” Chamba said.

“Like what?” I asked.

“I don’t know for sure. This is only a guess, but some Guides say people who need a light become Travelers. Other Guides say people who turn into light for this world become Travelers.”

I definitely wasn’t the latter.

“What do you think?”

At my question, Chamba stopped walking and stared far into the distance. It was as white as the fur of an albino rabbit in every direction. Standing on a road that was blanketed in a white light that simplified the chaotic urban landscape, without turning around to look at me, Chamba said, “People who are sad.”

After that, they started moving again. As we passed through a particularly snow-packed area, I walked, twisting my body at large angles like a person wearing a splint on their leg. Why did the granny in her eighties become a Traveler? Did she need a light? Had she been sad? Did she need someone to walk with her once she had died? Still, at least she lived long enough. As I was thinking that, a dark shadow fell over my head, like someone had altered the stage lights on a ceiling. The sunlight that had been following us was now obscured by a building supported by tall columns. The snow that had gathered on top of a gas line gave a sound like crumpling paper and fell on top of Chamba’s head.

“No one in the world has ever said they’ve lived long enough,” Chamba said, and then shook their head, like an animal ridding itself of moisture.

As we took a winding road between buildings, the familiar sights of Sogong-dong unfolded before us. Along the path lined with huge advertising billboards, we saw hotels and buildings of large corporations. The glass windows of the buildings, which all looked somewhat similar, were illuminated even brighter than the snow. Standing in front of a high-rise with a helipad, I counted the floors from the top and worked my way down, until I reached the floor where Semo’s office was located. I wasn’t sure if Semo had moved further up from the time I knew her. To reach the highest floor where no one would be able to invade her privacy—that was the life Semo wanted.

When I started seeing Semo, I was a full-time employee who’d been issued a new credit card without a strict screening process. From time to time, I’d go to the hospital for symptoms of insomnia and would receive a prescription for antidepressants, but I considered them emergency medication you kept at home like fever reducers or pain relievers. Semo was a consultant at some company that planned to acquire the company where I worked, as well as an attendee of a regular meeting where I readied the table and prepared refreshments. Semo always arrived first, wearing a monotone suit and a gray backpack, and quietly made conversation with me as I stood in the corner of the room. If anyone needs anything, they’ll let you know. Please sit down and wait, don’t just stand, she’d say to me.

Even though Semo wasn’t someone who could easily change her tone of voice whether she was in a meeting or on a coffee break, when she was with me, she had many facial expressions and showed her emotions. When she was sulking, her eyelids would go up as far as they could and her eyes developed straight edges. I liked seeing that. She was fourteen years older than me and looked over complicated documents about patent proceeds, but when my foot swelled because of wearing high heels or if I had to respond with a smile to an executive talking to me with a grip on my arm, her eyes became triangular and revealed her disapproval. Semo’s lower belly stuck out and she alternated between pairs of glasses that were all similarly designed and, when she kissed me, sometimes I smelled her wisdom teeth rotting. I liked that smell, too. Because I was the only one allowed to smell it. I liked the crescent mark on her left cheek and even the lower molar that had grown like it was lying on its side. I called the crescent scar, which looked like a smiling mouth, “Smiling Child.” I named the crooked tooth, “Lying-Down Child.” When Semo treated me badly, I pestered her to show me the children. Show me Smiling Child. Show me Lying-Down Child. No one knows about this except me, right? You wouldn’t show this to anyone else, right?

Back then, I would walk around Sogong-dong while waiting for Semo. If Semo told me she would finish up within the hour and come down, I would walk from her building to City Hall and wander around Deoksugung Palace across the street. Not knowing when Semo would arrive, I didn’t go inside the palace and instead went to the museum garden on the opposite side to look at the outdoor sculptures illuminated by floor lights. If Semo still hadn’t called, I would walk along Jeongdong-gil and roam about in front of the theater with all the posters of upcoming plays. I even walked up the hill leading to the US Embassy and along Doldam-gil, where the Salvation Army Headquarters

was. Even though I’d left work right on time, as I walked around, the night had grown dark; exhausted and starving, I would make up my mind not to forgive Semo easily when she showed up. I won’t stop being mad even if you show me Smiling Child, even if you show me Lying-Down Child. Even though I was determined, as soon as Semo showed up, my displeasure vanished for the simple reason that she had come to me; Semo, after spending less time with me than I had spent waiting for her, pulled out her laptop and went back to work.

The Semo I remembered: a comfortable shoulder to rest on, breath that smelled like ripe, sweet persimmons if you faced her and inhaled, thin hair that split easily, an upper lip like the number three on its side, the sound (like the cry of an archaeopteryx) she made when I took her in my mouth. A hand with joints that puffed up like frog legs if she worked too much, the pickle she picked up and ate with said hand, matching pajama pants of Keith Haring’s artwork, the line from The Little Prince that we repeated like a spell whenever one of us wanted to be demanding like a child. If you please, draw me a sheep! If you please, draw me a sheep! How else can I describe Semo? A fraidy-cat who didn’t like seeing the premature gray hairs below her ears and was scared of lying down with her mouth open at the dentist’s. A closet I might tell my mother about if my father ever died, but one I’d completely hide from the public arena. A divorcee. A person who said, An identity isn’t something you discover for yourself, but something that makes itself known, even if you don’t say anything aloud. Worrying if someone will find out is actually a big strength because you’re forced to read people. Strength as an identity. If I said to Semo, You’re not some herbivore prey in the Serengeti, why do you view the whole world as your enemy? Semo replied that that wariness was her only defense mechanism. After all, shouldn’t I have at least one horn to attack with when I’m about to be eaten?

Would Semo have gone to the dentist? Did she get her wisdom teeth removed?

What kind of reaction would she have if I showed up in her dream?

“I guess I should start with a text,” I told Chamba.

A man with steam rising from the nape of his neck moved past us pushing a snow shovel. Behind him, another worker scooped calcium chloride from a sack and scattered it on the ground. Chamba moved where the stiff, white kernels were scattered and scurried over them.

“A notification will go off in her dream. And then she’ll see my text.”

Good night to you too.

Just like the text Semo sent me after our second date. Good night to you too, as though I had been the one to say good night first.

“I’m going to tell her I’m doing well, that she shouldn’t worry. That I’m in heaven with an angel…”

“That you’re where now?” Chamba asked, their footsteps crunching.

“Aren’t we in heaven?”

“This is City Hall.”

I looked up high in the sky, as though Chamba had arrested my gaze. The old City Hall building with its dome-shaped central roof stood in front of us. A light layer of snow spread evenly like cream along the stone masonry part of the building, its thick wooden door shut. There were wooden signs that read Keep Off Grass, Mind Garden, Music Fountain leaning against the snowy stone steps, like someone’s idea of a joke. Snow settled into the Gungseo font engraved into the wood. When did we arrive here? I was lost in memories of the saag curry I had eaten with Semo. I was thinking of the garlic naan and the thick lassi that she liked so much.

I turned around and looked at the path we had just walked. The people who had been clearing the snow had disappeared. Along the path they had followed was a semi-circle of arborvitae planters. A dark pink light came from the planters’ circular edge, like it was tearing through the white of the snow. Before I knew it, Chamba had gone to stand in front of the light.

Where in my imagination did such a color come from? It was a gaudy, garish, outrageous opera-pink, like artificially colored candy or rubber gloves drawn with pastel crayons. Snowflakes fell into the light. As soon as they landed, they looked briefly like flower petals, and then melted from the light’s heat. That light, that glare of color that made that light, that song coming from a jukebox dunked in acrylic paint—they were all beautiful and unrelated to me.

Scarlet alpenrose, blooming after it sips on dew. Das Oberland, Oberland. Berner is beautiful.

It was a habit, not my imagination, that made me recall the lyrics and music that followed just by listening to one measure of that song. A familiar line of thought that my thirty-something-year-old self had walked along with. I still did not know the meaning of Das Oberland nor did I know exactly where the Bernese mountain village was, but after I died, I learned that the scarlet alpenrose in the song was a rhododendron that grew in the Alps. A wooden sign stuck under the pink light: Alpen rhododendron (alpenrose). As a member of the Rhododendron genus, it grows in the alpine regions and is known as Rhododendron ferrugineum or the snow-rose . . .

If I didn’t even know that, how did my imagination know about it? It’s over for me, so what was I doing here right now? I was dead, so what was I still afraid of? What if there are feelings that won’t die even though I’m dead? What if a melody still lingers on the tip of my tongue even after the song is over? What if I had to visit someone’s dream and say something?

I looked at Chamba. Chamba was standing next to me, goggles perched on their forehead.

“What if she thinks I died because of her? That it’s her fault, that because she and I lean this way, because we’re of this orientation, that this was the only way things could end?”

I took off my gloves and wiped my eyes. Blocked by the stone building of the old City Hall, the breeze blowing from the sprawling plaza surged over the arborvitae planters that we were standing next to. Chamba’s hair, which lay in the direction of their widow’s peak, grew rumpled in the wind.

“Can’t you go tell them that I’m dead? Just one call to the police station,” I asked, rubbing my eyes. The more I rubbed my eyes, the more clouded my vision grew, turning into a spectrum of alpen rhododendrons in pinks, yellows, greens, blues.

“I’m a Guide. I sleep so deeply that I don’t even dream,” Chamba responded.

Without opening my eyes, I raised my voice like a sudden note in a yodel. “Sure, Mx. Chamba Pumba! Look at you in your performance wear, and me in this windbreaker that barely covers my butt! All you did was put dried seaweed on your fried rice and gobble it down, you didn’t care whether I choked or not on that tteok!”

So many colors swam before my eyes that I felt faint. I grabbed Chamba’s arm.

“Your arm has a zipper pocket too. Where did you get these clothes?”

Chamba stood for a moment without saying a word, then walked up close to me. They blew away a bit of the powdery snow on my face.

“I’m sorry, but I left my banjo back at the tteokbokki restaurant.”

*

Chamba said their duty as a Guide was to make sure Travelers didn’t get lost in their own imaginations. But before they were a Guide, they too were a Traveler and, back then, in the sultry weather of an impending monsoon season, they walked along the border of city and province to reach someone.

“I went to a red chili pepper field,” Chamba began. “My mother’s field, where she alternated harvesting peppers and onions every year. It was summer so the soil was red and fertile. Mother wore a floral sun hat with a visor and was pulling weeds. She was bent over in her rubber boots, digging at the soil with a hand plow. I took charge of a furrow behind her and started pulling weeds too. Insects buzzed and buzzed while sweat rolled down my skin. Then Mother said we should have lunch and pulled out frozen barley tea, brown rice, and yesterday’s grilled mackerel from the cooler bag she had brought from the house and we made lettuce wraps. We ate them with the red chilis we had just plucked. We had been eating for a while when we heard an oink-oink sound coming from the end of the furrow. A black piglet was running toward us, scattering soil everywhere with its hooves. It launched itself into my mother’s arms and rubbed its flat, wet nose all over her face. Like it was kissing her all over. After that, she woke up.”

We were walking back from City Hall, through Sogong-dong and toward Namsan Mountain. As always, Chamba and I walked an arm’s length apart, each of us leaving our own set of footprints.

“It’s a dream suggesting that you buy a lottery ticket, isn’t it? A pig dream.”

“That’s right. After Mother had that dream, she went to a lotto shop. She called me to ask whether she should get one from the automatic lottery machine or the semi-automatic one, but I didn’t pick up, of course. I wanted to create a nice dream for her. A dream that would make her smile when she woke up. A dream that would make her want to buy a lottery ticket. I was born in the Year of the Pig, you see.”

The two-tiered, snow-covered tile roof of Sungnyemun Gate looked close. The cars that used to move along its five-pronged road had disappeared; in the middle, stonework that supported the pavilion remained isolated like an island.

Looking at the snow packed in white lines between each stone, I asked, “So what do you do after you’re done visiting someone’s dream?”

“Is there something you want to do?”

“What have other Travelers done?”

“Most of them keep doing what they were doing,” Chamba answered. And then, as if to say, It’s okay to mention this much, they added, “To take a well-known person as an example, Van Gogh is said to have painted. Virgina Woolf and Jeon Hyerin kept writing. Deleuze read books, Leslie Cheung watched movies.”

“Who?”

“Famous people. You might know them.”

“I’m not familiar. Though I do know Van Gogh and Leslie Cheung.”

I didn’t turn my head but I felt Chamba’s gaze on me.

“When a singer awakens, they sing and dance. Because that’s what they loved best. Farmers plant crops and merchants sell them. There was a Traveler who was a fund manager before they awoke and they sat at a desk and used the computer and made phone calls.”

“Why did that person become a Traveler, I wonder? The fund manager.”

“Parentheses,” said Chamba.

We walked along the wall of Sungnyemun Gate. On the opposite side, we could see the arched gate of Namdaemun Market. Somewhere beyond, there would be people selling goods, doing some window shopping, and eating doughnuts and fish cakes, but to me that sort of hustle and bustle felt like something that had happened a long time ago.

The road grew narrower as we began our ascent up the mountain, and Chamba, looking at me, asked, “It’s up there, right?”

I told them about an autumn day when I walked along Namsan trail, covered in fallen gingko leaves, the memory of my mother and I going inside a supermarket and drinking coffee milk. I wanted to see my mother drink in her own unique way the Coffee Pori she had enjoyed so much.

Namsan Trail’s Last Supermarket, just as its name said, was at the end of the Sowon-gil slope. When I pushed open the frosty glass door, a rusty bell dangling from it let out a ding. The shop owner, cocooned in a faded blanket, saw us and turned down the TV volume. When I told him that we were looking for coffee milk that came in triangular plastic packs, the shop owner pointed to a refrigerator that sported a Pepsi-Cola sticker. I walked past, a low wooden shelf stocked with bread, snacks and chocolate, and opened the refrigerator door which had another rusty bell hanging from it. The moment I pulled out the coffee milk, I realized how I’d be able to visit someone else’s dream. The spirit of my dreaming mother, my spirit visiting her dream, and Chamba’s spirit that connected us both, came together like three straight lines at the top vertex of a triangular pyramid. The planes of those spirits, stretching in three different directions, looked like the triangular pack of coffee milk sitting in my hand. The feelings that had led me to this place—the sadness that was both darker and brighter than me—supported us like the base of the pyramid-shaped coffee milk.

“Here, a straw.” Chamba tapped me on the shoulder and handed me a straw they had gotten from the shop owner.

“Now, look carefully. Not everyone can get this right.”

I crouched in front of the shelf and removed the straw wrapper with my teeth. I angled the pointy part of the straw downward and aimed at the sloping polyethylene film containing the coffee milk. Pierce the plastic and stick in the straw in one fell swoop, before you can blink, just like Mom!

“It didn’t work. Mom was good at this.”

I straightened out the crooked straw and tried again, but managed only to ruin its shape further. Beside me, Chamba used scissors to cut the corner of the milk carton.

“Let’s make things easy for ourselves. Use a tool.”

Chamba put the carton to their lips and drank without using the straw. Their clothes rustled as they raised an arm and cracked their neck. Snow melted into pools of water around their black sneakers. Behind them, a knee-high kerosene stove radiated heat; on top of its steel plate, a dinged-up brass kettle let off steam.

“Please make it stop snowing now,” Chamba said, stepping outside.

The awning we were standing under was bulging under the weight of the snow. Chamba noted the footprints we’d made on our way up were already covered up by the snow and that they might as well be rolled like a snowball because they couldn’t walk anymore.

“It’s not cold, though. Should we have a snowball fight?”

I sat down and started packing snow.

“I hate getting my clothes wet more than any—”

Before they could even finish, my snowball hit the nape of Chamba’s neck and exploded.

Making sure to still maintain dignity even in the face of injury, Chamba removed their gray polka dot scarf. I could see their throat. I checked whether or not they had an Adam’s apple. But the first thing I saw was Chamba’s wound. There were scars on their neck from when they had pulled their own plug. Alone, in a car, so they wouldn’t wake again. Just like listening to one measure of a song made me automatically think of the next measure, Chamba’s time drifted toward me.

I went up to them while they were dusting off their scarf. “I have a question.”

“My clothes? I got them when I started as a Guide. I don’t know where they’re from.”

“No, I mean, when I’m visiting the dream, what will you do?”

“What will I do? Nothing, that’s what. I’ll rest.”

I suggested we go back to the tteokbokki restaurant to get the banjo, but Chamba said to just leave it since they didn’t know how to play nor did they have any aptitude for music.

“Then I’ll rest, too,” I declared.

I bent down and rubbed snow into my face like I was washing it. The snow smelled of rusted iron. A piercing cold spread from my throat to the crown of my head. It felt like I could be buried under the snow and erased in one go. I realized that even in death, I hadn’t been able to rest. Because I had been searching for the reason, clinging to the cause in this causal relationship, that I hadn’t even fully enjoyed the effects of death. I wanted to put the existence of me in empty parentheses. I didn’t want my dead self to be found anymore. I didn’t even care whether the details of my death or the accomplishments of my life would be concluded without misunderstanding. Instead, I wanted to visit the dreams of the people I had ties to and show them a good time. I wanted to visit Semo’s dream and see Smiling Child, then open her mouth and see Lying-Down Child. Then I’d take her to the dentist and we’d get her wisdom teeth extracted completely without pain. I’d apply ice to her swollen cheek and then melt her frozen cheek with mine. Like the time Semo ran to me after I had been waiting outisde for a long time, and melted my frozen cheeks with her own. I’d meet Gyuhee at Dongbaek Tteokbokki and we’d put sweet corn and rice in the tteokbokki sauce and eat stir fry. Should I make a high chair and a kids’ menu for Gyuhee’s children? With the strength of my imagination, for the joy I remembered. It felt like those dreams had already arrived and were just waiting for the right person to dream them. Perhaps those dreams would linger even longer than me, floating through their hearts.

Could I make a dream like that on my own? Wouldn’t coverall-wearing Chamba mark my location in pink stripes? My snow boots are completely soaked and my socks are damp too, I don’t want to walk anymore.

Chamba and I rolled down the snow-covered ground. Like snowballs, we rolled and tumbled all the way down. Like a dead leaf that didn’t fear the wind, like a snowflake that didn’t have to worry about what happens to it once it fell, we rolled and rolled and rolled down the slope. I went first, Chamba followed. We were two round billowing pigs, adding more snow to the snow.

So

I hope you have a joyful dream of me.

Tonight, I’ll go to you, Mom. I’ll visit your dream.

I’ll bring coffee milk with me. So please, stick the straw in for me the way you usually do.

Translated by Archana Madhavan

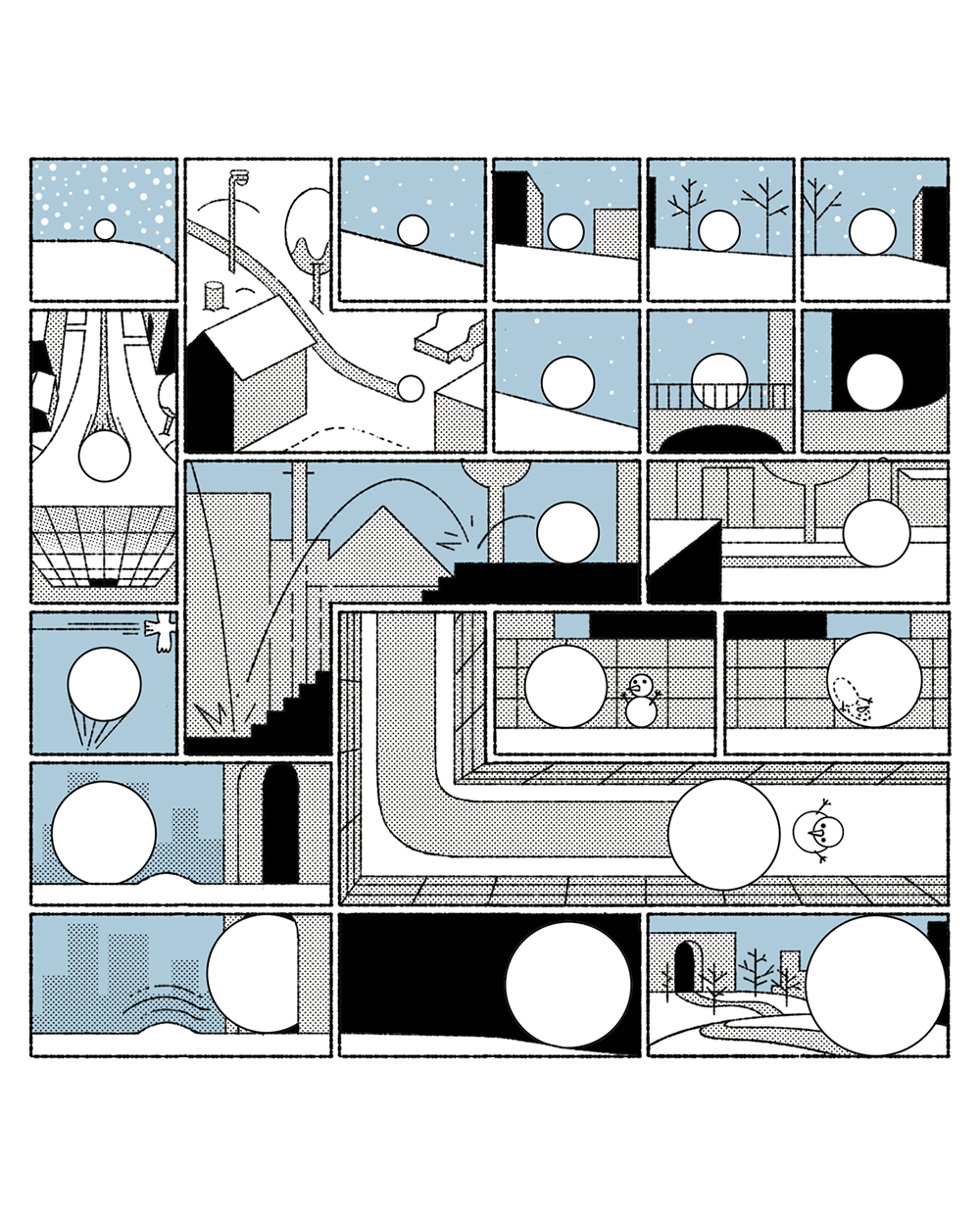

Illustration ©OMSCIC COMICS

Did you enjoy this article? Please rate your experience